Where Is the Voice of Faith about Canada's Indian Act?

Dear Reader: This is a two-part post. The first, is the short form; the second elaborates some of the history. Up to you to decide how far you will read. I write out of my experience in The United Church of Canada / L'Eglise Unie du Canada. But my concern is for all Canadian faith communities and their need to speak faithfully to the Indian Act society we still inhabit.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Part 1

It has become a growing conundrum for me that Canadian faith communities, and especially the Christian churches, have hardly raised their voices against the complex and costly colonial domination system, represented by the Indian Act, which is still coursing through Canada's societal veins today.

Summary History (for more detail read on in Part 2 below.)

A cursory glance at ecclesiastical history in Canada regrettably shows little theological analysis of the policies based on the racist Indian Act (1876 frequently amended). The Act famously eschews any and all governance and cultural traditions that were part of Indigenous life. It shuns the historic Treaties between Indigenous First Nations and the Crown.

The assumptions underlying the Act are frightening for most 21st Century Canadians, if they know them. It relies on racist 19th century doctrines proclaiming that Indigenous Peoples were inferior to the superior white, Euro-colonial settlers and therefore should be treated as dependent wards of the Crown. The wards were subjected to the supervision (subjugation) of Indian Affairs agents, enforced by the RCMP.

In the latter half of the 19th Century, colonial settlers focussed on building the nation and the growth of the Christian churches. The Indian Act expressed both political and religious opinions about how to overcome "the Indian problem". Indigenous Peoples were dispossessed from their vast inherited lands, confined to tiny and usually unproductive reserves, and deprived of essential cultural identity sources.

The story of Indigenous treatment at the hands of the dominating Settler society casts long, dark and frightening shadows on the “true patriot love” for Canada not “all of us” sing about in the national anthem, absent of any recognition that “our home” is “on native land.”

What troubles me about this sordid story is that the Church of which I am an ordained member has not been heard raising its prophetic and theologically-based voice then, and not even now, against the 150-year old system of subjugation prescribed by the Indian Act.

Historically it is easy to recognize that the values informing the aspirations of colonial society and the values espoused by the Christians churches of that era were vastly overlapping. And while today’s churches have repudiated the 15th century’s incredible Doctrine of Discovery and the terrae nullius lie, the malignant effects of these papal doctrines still survive in the Indian Act.

At its core, Christendom, the totality of Christianity institutionalized in the Western world including its Canadian outposts, felt called to Christianize and “civilize” the entire human family, especially presumed inferior indigenous and "pagan" peoples, into superior European ways through colonization and missionary endeavors.

United Church Ways

To be sure, the UCC has repudiated the Doctrine’s imperialism and the anthropology which pits races against each other. Our theological commitments forbids us from assenting to racist superior-inferior doctrines. We have a vital tradition of speaking bravely and in timely fashion of God’s unconditional and eternally persistent love for the entire human family in Creation.

All humans, we confess, are “made in the image of God” deserving the blessings of abundant life, as they in their context can embrace it. Unconditional love and respect for human diversity are core understandings of the Gospel. Divine law and the Way of Jesus contradict any laws, mores, and religious doctrines that allow powerful interests and people to impose their ways on other humans. “We sing of the Creator, who made humans to live and move and have their being in God.” As a church we have committed to working “with God for the healing of the world, that all might have abundant life.” (quotes from “A Song of Faith” – A Statement of faith of The UCC/EUC. https://united-church.ca/sites/default/files/song-of-faith.docx )

This collaborative healing work took many forms. We found ways to undermine the fascist brutality of Pinochet’s Chile and to provide safe places for its refugees. We shared efforts with Christians in "second world" Soviet-dominated countries like East Germany to break down brutal walls of separation. We raised our collective voice against antisemitism. and have actively sought a future of justice-based peace for Palestinians to live in a healed relationship with Israel. Through Project North, we campaigned in support of the Berger report against oil exploration and the proposed pipeline up the Mackenzie River valley threatening to destroy Indigenous territories and communities. We worked hard to counter sexism by reforming the Church as an egalitarian organization with women and men in partnership roles and commitments to the Gospel. We have confessed our homophobic past and recognized God’s call to discipleship and leadership for LGBTQ2 friends and companions of Jesus (1988). We embraced the "inter-cultural" vision for the Church - and society! We have confessed and apologized to United Church Indigenous participants for the disrespect with which we treated them, their spirituality, and their ways of being faithful (1986). And we apologized (1998) and paid reparations for our part in the Indian Residential Schools (2006), including the inter-generational damage and suffering this system caused. We expressed our intention to be less “church oriented” and more “world oriented” together with other people of goodwill to work with God…for the mending of creation, calling us to see the world through God's tears….” (https://ecumenism.net/archive/docu/1997_ucc_mending_the_world.pdf) And much, much more.

Our Church has not shied away from courageous (and often costly) witness to the liberating and healing Gospel of Jesus Christ for all people.

Yet despite all this necessary and faith-based witness, I am left with the question: where is the Church’s testimony against the inherited and still operative legislated framework and policies – the Indian Act - that afflict our nation and burdens Indigenous Peoples? I am personally puzzled by this void.

Contextual Theology

In the 1980s, I co-taught Canadian contextual theology at Emmanuel College in Toronto. My partner, Professor Harold Wells, and I were committed to the understanding that Christian theology must be contextual. Douglas John Hall, a leading theologian of the UCC, based in Montreal defined it thus: “in [the contextual] mode of reflection which we call Christian theology, there is a meeting between two realities: on the one hand the Christian tradition, namely, the accumulation of past articulation of Christian concerning their belief, with special emphasis upon the biblical testimony; and, on the other hand, the explicit circumstances, obvious or hidden, external and internal, physical and spiritual, of the historical moment in which the Christian community finds itself. Theology means the meeting of these two realities.” (in Toronto Journal of Theology, Vol I/1, Spring 1985. P. 4)

The surprising question for me now is why in our classroom conversations then the contextual relationship between the Settler society, of which all in the class were part, and Indigenous Peoples were not on the agenda, In the classes, we discussed inherited theological convictions and historic social passions and actions of the Church in relation to issues of poverty, homelessness, workers’ rights, the "Christianizing of the social order", and much more. I do not, regrettably, remember any conversation then about or related to the repudiated Doctrine of Discovery and terrae nullius concept upon which Crown sovereignty over Indigenous peoples depends and nothing about the Church's witness against the societal order prescribed by the Indian Act.

Perhaps in our classroom discussions we shared the blinkers that pervaded 20th Century Canadian mainstream. There seemed to be an agreed upon ignorance of the reality of Canadian society's treatment of Indigenous People. Somehow the Indian Act and its dire consequences seemed a marginalized given – “it is what it is”. In our time, we just took the arrangement for granted.

Yet, change was happening. First Nations people within the Church were calling for justice. The Church offered an Apology to Indigenous members of the church in 1986 admitting “We tried to make you be like us and in so doing we helped to destroy the vision that made you what you were.” The Residential Schools horror was beginning to be understood. Soon the churches and federal government would be taken to court for the violence and sexual abuse experienced in those schools.

We had, however, not come to the realization that Indigenous People of Canada were living in a society in which the rules, the opportunities, the properties, and the money were controlled by Settler society, while Indigenous peoples inherited the biblical “crumbs under the Canadian table.” We still lived as if it was simply their lot!

Apartheid

Remarkably, even as we protested apartheid in South Africa and the General Council of The UCC declared apartheid a “heresy” (the only doctrine the UCC so labelled), we did not make the connection we ourselves were living in an apartheid society.

But others did. As Brian Giesbrecht, a retired Manitoba Provincial Court associate chief judge (1976 to 2007) observed in a Troy Media posting of 11 September 2018:

In the 1940s, when white South African politicians were designing a system that would keep people of different races separate, they came to Canada to study our system: its Indian Act, status cards and reserve system. They went back to South Africa and created a system that modelled its homelands largely on our reserves and its status cards, largely on the cards Canada hands out to status Indians.

The irony of Canadians passionately denouncing South Africa’s apartheid system, while not noticing that we had an apartheid system of our own, was not lost on either South African politicians or Canadian Indigenous politicians. In fact, during the height of the demonstrations against the South African regime in 1987, South African Foreign Minister Glenn Babb and Peguis First Nation Chief Louis Stevenson teamed up to stage a press conference pointing out this hypocrisy.

Change

We were “hoist with our own petard”. Jean Chretien's 1969 White Paper on Indian policy once more proposing the assimilation of Indigenes Peoples evinced huge negative reactions by Indigenes Peoples and supportive settlers. It started a trend. Government inertia was giving way to informed analysis and energetic challenges and litigation by persevering Indigenous bands. The comprehensive Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) merited serious study and pursuit of its recommendations by all Canadians, including Church councils. It became a beacon, even if governments and churches didn’t implement its recommendations. In 1998, the United Church apologized for its part in the Residential Schools system, having been responsible for 15 residential schools operated between 1849 and 1969.

https://united-church.ca/sites/default/files/apologies-response-crest.)

Indigenous relations were increasingly becoming prime discussion topics. Supreme Court judgements in favour of Indigenous claims and rights moved the dial on government recalcitrance. Indigenous people were gathering to discuss and act on their situation in Canadian society . It was beginning to be a time of ferment.

But the core issue – the Indian Act system - hardly came into societal focus. Lots of individual issues were being addressed, frequently with the federal government responding with cash grants. But the framework, the underlying discriminatory constitutional order remained the same. The Indian Act seemed impregnable.

I confess my personal failure in this matter; I am ashamed as a Canadian, a Christian, and as a member of the Church that we didn’t own our country's apartheid system, that we tolerated a system that has the marks of cultural genocide, that we failed to raise our prophetic voices to call for an appropriate end of this sinful Act and a new basis for the Indigenous and Settler relationship. We still haven’t.

Where to?

It is not too late for the United Church and all the faith communities to confess this hypocrisy and raise the voice of faith for an end to the system represented by the Indian Act. This settler imposed legislated order has too long dishonored the Crown* and tormented Indigenous Peoples. Calling for its end is a Gospel imperative if we - the UCC and other faith communities - are to be faithful.

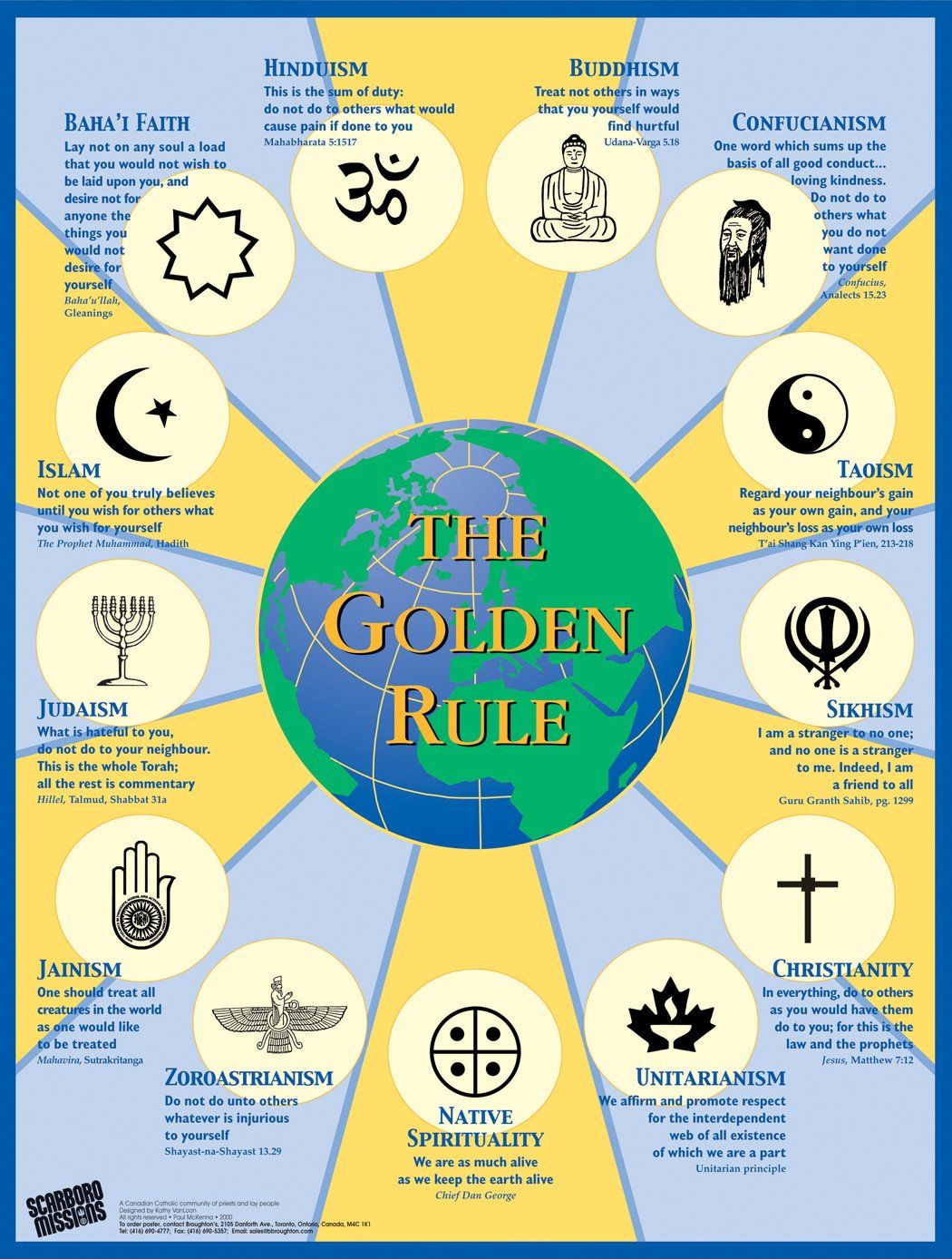

I hope that the second 100 years of the United Church will entail a sacred commitment to live in friendship and just peace (Two-row Wampum) with Canada’s Indigenous Peoples - a transformed relationship. I would be even happier if it were an inter-faith commitment - the voice of Canadian faiths calling for a new way to be Canada. For Christians, such a new way would include once and for all ridding Christendom of its worst theological arrogance, its misunderstood mission, and its hubris. Instead it would signal an embrace in the Spirit of the Way of Jesus.

I hope the 150th Anniversary of the Indian Act in 2026 will mark its end, its repudiation, and the launch of new, mutually respectful negotiations with Indigenous representatives for a new Covenant or Proclamation or Treaty - a transformed relationship, that honours previous treaties, legal judgements, and the Crown’s* fiduciary responsibilities to Indigenous Peoples. The whole of Canadian society would benefit.

May the Spirit forgive, reconcile, transform, and free us all to “work with God for the healing of the world that all might have abundant life.”

(Song of Faith)

* see below for John Ralston Saul's clarification of "The Crown" in the Canadian context.

Part 2 - a thumb nail history

It wasn’t always an asymmetrical relationship of power over subservience. The earliest Europeans .landing on northern Turtle Island’s beaches quickly learned that their survival could only be assured by cultivating relationships with Indigenous Peoples. Cooperation and eventually trade was paramount, though peace was a fragile flower and atrocities on both sides punctuated the complexity of the relationship.

The Great Peace of Montreal (1701) marked the beginning of a period of Haudenosaunee – French agreement, allowing the French authorities freedom to focus on defenses against British expansionism. The defeat of the French forces on the Plains of Abraham in 1759, however, confirmed British dominance of North America.

George V's Royal Proclamation of 1763 asserted the victor’s sovereignty over all (a factor in the American Revolution) and provided clear understanding of the Indigenous occupation (but not sovereignty) of the territories. European settlers were permitted only to acquire land from the Crown and the Crown obtained land from the Indigenous peoples. The Proclamation laid the basis for nation-to-nation treaties.

The Treaty of Niagara (1764) confirmed the British – Indigenous alliance as a nation-to-nation relationship and resulted in First Nations allied with the British in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812, ensuring the survival of British North America – Canada!

In the first half of the 19th century, the relationship between the British settlers and the Indigenous Peoples might be defined as mutually beneficial, if not always complementary. The Indigenous way of life was threatened by the increase of settlers, but some mitigation of the threat came with the efforts of missionaries and teachers often working with new Indigenous converts to educate and improve social conditions.

Later church representatives competed (shamefully) in their vigour to bring their particular denominational brand of the Gospel into the lives of Indigenous peoples. Significant numbers converted to Christianity.

Living conditions improved for many and death rates declined. John Grant, a pre-eminent Canadian church historian, notes: “Never in Canadian history has conversion to Christianity been of such evident benefit to Indians as in Upper Canada during the second quarter of the nineteenth century.” (Grant, John Webster. Moon of Wintertime – Missionaries and the Indians of Canada in Encounter since 1534. Toronto, U of Toronto Press. 1984. P.91)

"The Indian Problem"

But as the settler population grew, the ways of Indigenous people were deemed increasingly incompatible with settler values and lifestyles. The dominant governing system – British – deemed it to be an “Indian problem” that needed solving. The notion that Indigenous communities might the determine the situation to be an “settler problem” was not entertained.

In 1842 Governor General Sir Charles Bagot commissioned a report which proposed solutions to the Indian problem. “Significantly, it recommended the establishment of Residential Schools to separate children from their families and ensure their ‘civilization.’” Assimilation and education of the Indigenous children became the plan to create a uniform society. (source: Indian Residential School History & Dialogue Centre. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/objects/9431)

“Civilization” carried with it the assumption of Christianity not only in the government report but also in the mind of the missionaries and church leadership. Would this double conversion open the doors to the new mainstream society? Not likely. Says Grant:

“During this period … a subtle but significant shift was taking place in the missionaries’ conception of their task. Instead of seeking to help Indian converts to make a voluntary adjustment to a new situation, they attempted increasingly to impose Western values whether the Indians were willing or not. Other civilizers, including the Aborigines’ Protection Society, were moving in the same direction. These views were embodied in the Civilization Act of 1857, which contrary to the desire of tribal leaders provided for the voluntary transfer of individual Indians to white status.” (Grant, p. 94)

Assimilation in the guise of “civilizing” and “Christianizing” effecting cultural genocide - this became the dominant intent of both church and state. The colonizers’ doctrine of superiority pervaded settler society’s attitude and behaviour. Patriarchal racism pervaded the colonial society while Indigenous society crumbled.

Nation and Church Building

In the latter half of the 19th century, nation building became the dominant agenda of the colonial government. Treaties with Indigenous Peoples were negotiated as nation-to-nation commitments, but were soon undermined by government failure to honour the terms. Moreover, government advanced the unilateral conclusion that in signing the Treaties, Indigenous Peoples had traded away their lands to the Crown.

With Confederation, the nascent government with the authority of the Crown took responsibility for Indigenous matters. The British North America Act of 1867 assigned to the federal government the care and well being of Indigenous Peoples. Negotiated treaties, reflective of the nation-to-nation relationship with the Crown, were soon superseded by legislation more in tune with the dominant sentiments of settler society.

The Indian Act - "solving the problem"!

In 1876 the Indian Act was proclaimed with its racist policies. (Resource: Bob Joseph, “21 Things You May Not Know about the Indian Act, Indigenous Relations Press,2018.) The Annual Report of the Department of the Interior for the year ending 30th of June 1876 outlined the operative philosophy:

“Our Indian legislation generally rests on the principle that the aborigines are to be kept in a condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State…clearly our wisdom and our duty, through education and every other means, to prepare him for a higher civilization by encouraging him to assume the privileges and responsibility of full citizenship.” (Source: Sessional Paper, 1877, vol. 7, no.II, Xiv)

Prime Minister John A Macdonald in 1883 made clear in Parliament the intent of the Act’s educational provisions – not withstanding Treaty provisions or the Royal Proclamation of 1763:

"When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly impressed upon myself, as head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men." (May 9, 1883, First Session, 5th Parliament, 1107-8; cited in Wilson Raybould, p.97)

An Alberta Methodist Commission saw the government's unjust policies as fulfilment of charity: "The Indian is the weak child in the family of our nation and for this reason presents the most earnest appeal for Christian sympathy and cooperation.. We are convinced that the only hope of successfully discharging this obligation to our Indian brethren is through the medium of the children, therefore education must be given the foremost place." (Cited in Wilson-Raybould, op cit, p. 94)

As late as 1921, Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent-general for Indian affairs, was able to declare: “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is not Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the object of the Bill.” (Cited in Wilson-Raybould, Jody: True Reconciliation. P. 91.) A better definition of ethnic cleansing would be hard to find.

State and church – settler culture as a whole – were influenced by biological theories that promoted beliefs that some races were superior and others inferior. It was not hard for Anglo-Saxon Caucasian Christians to believe that they were the superior race and that the inferior Indigenous peoples might die out, or, at least, would need to careful, charitable support to assimilate into the dominant culture. (see Airhart, Phyllis, A Church with the Soul of a Nation, p. 8).

Christendom

Theological support came from Christendom’s history of institutionally-driven dominating expansionism, as articulated in late 15th and early 16th Centuries pronouncements like the Doctrine of Discovery. The 18th Century emergence of the modern missionary movement relied heavily on an interpretation of the Great Commission (Matthew 28:18-20) that reinforced Christendom's religious and cultural inclinations, but underemphasized Jesus' humbler, accepting Ways as revealed in the Gospels.

At the time of Confederation, church and government policies were aligned on these theologically dubious assumptions. Both politics and religion agreed on the conviction that Indigenous Peoples were legally incompetent (as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples observed) and should melt “through education and every other means” into the higher civilization of the dominant Euro-colonial settler culture of the new Canadian nation.

Nothing should impede the way forward in building a “civilized” Christian society from coast to coast and eventually to the third coast – the north. In 20th Century parlance this is described as cultural genocide and, increasingly, simply as “genocide of Indigenous Peoples”. The shared solution to the "Indian problem" was to erase Indian-ness!

Dispossessing the inferior race of their native lands and the potential wealth of this incalculable inherited asset was, of course, key to their erasure. Postage-stamp sized reserves were held by the Crown for the “exclusive benefit” of Indigenous peoples, but the vast territories beyond were deemed “Crown lands” by which to finance and populate the new nation.

Dispossession led to: economic deprivation, spiritual uprooting, psychological wounding, source of food, and cultural alienation; while educating the children away from their communities assured the efficacy of the policies for the long term..

Christian churches – Methodist, Presbyterian, Anglican, and Roman Catholic - rushed to take on the educational role by staffing and maintaining the Residential Schools system. Under-funded, poorly staffed, badly supervised, unhealthy environments - the plight of Canada’s Indigenous people worsened (fulfilling the prophecy of the false biological theories), now specifically burdening their children with the curse of the de-Indianizing process.

The actual patriarchal relationship between Canada’s Settler Society and Indigenous Peoples was articulated in the Indian Act undergirded by the culturally-accepted convictions of the Doctrine of Discovery. It still is because the Indian Act still is.

To be sure much has changed. A new constitution in 1982 affirmed Indigenous inherent rights and treaty rights. Supreme Court judgements regularly unmask federal and provincial usurpation of Indigenous right and land claims. Governments were forced to repeal unbelievably cruel, and often petty, rules and amendments to the Indian Act. The amazing persistence and patient courage of Indigenous leaders pursued justice and gained it. The diligence and creativity of many Indigenous scholars, lawyers, artists, politicians, teachers, advocates, and leaders made it increasingly difficult to dismiss Indigenous challenges.

But the Indian Act still is! In 2026 it will be 150 years old.

A Time to Raise the Voices of Faith

Where are today's faith communities in this unwelcome saga? There were moments in history where there was some semblance of being concerned for the well-being of Indigenous people facing the Euro-settler invasion. But as we’ve noted, this turned into a concerted effort to erase “Indian-ness” from the culture – the racist genocidal apartheid policy.

The churches were able to acknowledge their sin and their contribution to the suffering, wounding, and death of generations of Indigenous children in the Indian Residential Schools system. The Settlement Agreement (still not fully owned the Roman Catholic Church) and apologies were important steps toward atonement for this particular inter-generational crime.

All the denominations have expressed some form of contrition – to Indigenous members of the church for disrespect of their person and faith; to survivors and families of Residential Schools for the harm done to them; to the general public by repudiating of both the Doctrine of Discovery and terrae nullius.

But the fundamental issue, I believe, still has not been addressed – at least not by my denomination, the United Church of Canada. The Indian Act with its societal implications is still is in place. It continues to defile and betray the Honour of the Crown*. It still inflicts its worst on Indigenous Peoples and haunts settler society. It is still sinful, vile legislation.

It is time for the United Church of Canada - preferably in partnership with other faith communities - to repudiate the Indian Act and demand that the government of Canada on behalf of the Crown* – i.e. all people of Canada - begin the process of replacing this criminal document by a new, justice-based settler-Indigenous negotiated framework of relating, respecting the Treaties, inherent rights, hard-fought judicial judgements, and the Crown's fiduciary responsibilities owed to Indigenous Peoples..

The two-row wampum symbol for respectful friendship and just peace in perpetuity must inform the negotiations and the new Covenant/Proclamation

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

· John Ralston Saul defines "the Crown":

“The Crown is the people. The people are the guarantors of the state. The governor-general is the protector of the Crown, that is, of the people. This is not about money or law or soldiers. It is about a role above power, a concept of the state above interests. … A meeting with the governor-general present automatically invokes the state, the Crown, the people. And the Crown automatically invokes the Honour of the Crown, a concept given its Canadian form in such historic Supreme Court decisions as Guerin in 1984, Sparrow in 1990 and, most recently, the Manitoba Metis case in 2013. …

What is the Honour of the Crown? It is the obligation of the state to act ethically in its dealings with the people. Not just legally or legalistically. Not merely administratively or efficiently. But ethically. The Honour of the Crown is the obligation of the state to act with respect for the citizen.” (Source: John Ralston Saul, The Comeback. Toronto, Viking Penguin Book, 2014. P. 33).