Donna Sinclair • March 17, 2021

The Water of Life

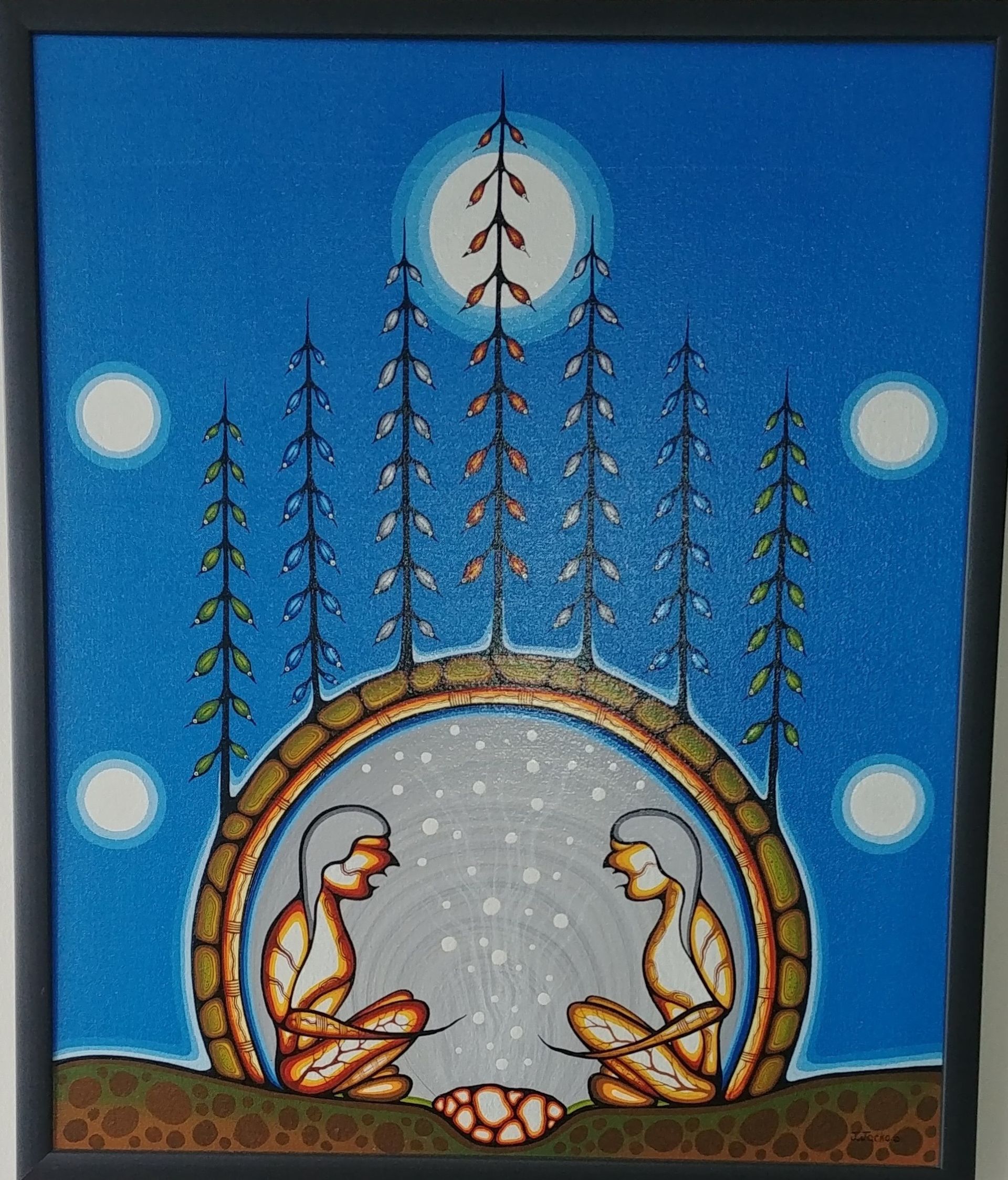

Image: Unsplash. John Duncan

This guest post first appeared in Mission Matters !!

-

A newssheet connecting the North Bay & area Mission Cluster with United Church people of faith. Issue #3 - March 2021.

The Water of Life

The ancient waters of her territory should be a world heritage site, according to Teme-Augama Anishnabai councillor Mary Laronde. Speaking about environmental racism on our Wet'suwet'en Witness webinar last fall, Mary concluded her extremely powerful presentation with a plea to develop a shared land ethic for nDaki Menan, their sacred land, the region settlers call Temagami. "None of us will survive if we don't have water to drink." We need to preserve its small untouched ecosystems, Laronde continued. In the midst of extraction and logging, "everything doesn't have to be taken."

Laronde's wisdom is crucial to all of us. In many ways, water symbolizes the chasm between colonial and Indigenous thought. For the former, water is simply a resource. It can be damaged by resource extraction or bottled and sold. For the latter - and in our own scriptures - water is life.

As a country, we have much to learn. One place to begin is with the boil-water advisories that are endemic to reserves throughout Canada, with 58 long-term advisories in 38 communities. This year's rapid commitment of billions of dollars to pandemic response - while necessary - threw into sharp focus the fact that water trreatment funding for reserves has never received the same priority. According to an investigation by the institute for Investigative Journalism, inadequate funding, bureaucracy, and racism get in the way. Indigenous Services Canada requires First Nations to take the "lowest valid bid price" for construction, for instance, which sometimes results in disproportionate low quality results. Required approvals of First Nations' feasibility studies often drag on until they are outdated by the time projects get the go-ahead.

Once built, underfunding means that on the majority of First Nations, water operators earn less than their municipal counterparts and are on call at all times. Lack of money for maintenance also means that equipment breaks down early or it is insufficient to begin with. On Nipissing First Nation, for instance, the treatment plant was deemed inadequate even as it was under consgtruction in 2009. Promises to adjust the design never materialized, and retrofitting now will be vastly more expensive. "I can move off the reserve a mile from here and West Nipissing doesn't have the same problem," Chief Scott McLeod told the Institute. "And if they did, it would be fixed, right? So when we talk about systematic racism, that's what we're talking about."

Expert and exacting research on reserve health would help. But "there's nothing. lt's a black hole," NDP MP Charlie Angus is quoted in Burn-Pieper's article. He says the lack of evidence is deliberate. "This is all about protecting the government from liability. If they don't track it there's no evidence."

The crisis in water on reserves is shocking. But its roots go far deeper than poor funding or sluggish bureaucracy. This endless emergency arises from the way we understand water: as a resource to be given or withheld and used as we wish - or as life, to be held sacred and protected. In recent clashes between corporations and Indigenous land defenders, the conviction that water is sacred is central. The Wet'suwet'en see the Coastal GasLink pipeline as a threat to their pristine water. The Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish and Musqueam similarly oppose the Trans Mountain pipeline. Many First Nations in Northern Ontario's ring of Fire fear the cumulative impacts of mining and road-building on their peatlands and rivers, even as others feel compelled by poverty to allow such activity.

We are called to name all these threats for what they are: environmental racism. The current federal government promises to end boil-water advisories, and has made some progress. But it's hard to heal lakes and rivers once the ecosystems that safeguard them are violated. Hence, this edition of Mission Matters. We suggest that, as people of faith, we listen carefully to Mary Laronde's wisdom and open our hearts to the sacredness of water. And that we support actions to end both boil-water advisories, and the water-contaminating projects that make them necessary.

- Written by Donna Sinclair with research, editing, and direction by the Indigenous Solidarity Team of the North Bay & Area Mission Cluster -

Some actions you can take:

Add your name (or faith community to a solidarity statement: https://cela.ca/call-for-a-moratorium-in-the-ring-of-fire-to-protect-watersheds-and-indigenous-rights/

Attend a (virtual) film festival and more: https://mailchji.mp/telus/movements-in-defense-of-life-film-festival?e=o86a2d1ab6

Petition & Pressure those in power: https//www.mcgilldaily.com/2021/01neskantag-a-first-nation-still-doesnt-have-clean-water/

Tell

MPs to redress environmental racism: https://www.kairoscanada.org/tell-canadas-leaders-to-redress-environmental-racism

Boil your water: try out life with a boil water advisory for up to a week: boil (one minute, rolling boil) all water used for drinking, cooking, brushing your teeth, washing your vegetables, bathing your toddler and feeding pets. Please let us know what this was like for you by emailing Kay Heuer, [email protected] (For more details on what to do, see: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1538160229321/1538160276874)

Read further: We are grateful to Concordia University's Institute for Investigative Journalism for much of the information in this Mission Matters. See

https://www.concordia.ca/artsci/journalism/research/investigative-journalism/projects/clean-water-broken-promises.html