A H Harry Oussoren • April 3, 2021

The Place of Theological Studies

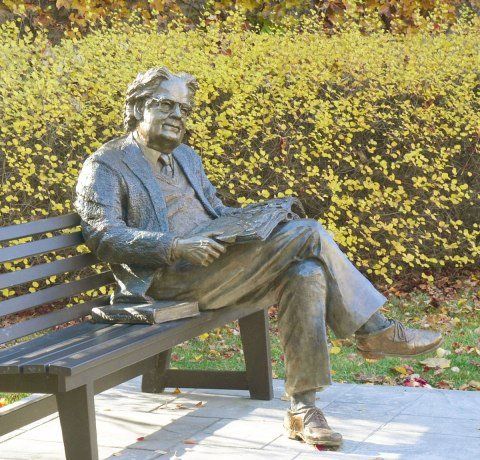

Rev. Dr. Northrop Frye (1912-1991)- straddling arts and theology at Victoria University (source: The Strand)

Theological Education – Learning from the Past #3[Continuing reflections with the guidance of Kenneth H. Cousland’s The Founding of Emmanuel College in Victoria University in the University of Toronto, 1978.Previous posts on this topic:https://www.minister.ca/theological-education-learning-from-our-past-2https://www.minister.ca/cultivating-theological-leadership]~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~Post 1925 UnionWhat could possibly go wrong?... I asked in the previous post #2. Here’s the answer:With the Union of 1925, virtually the entire Congregational, Methodist and Local Union Churches, and the Presbyterian Church – as institutions – united to form Canada’s largest Protestant denomination, The United Church of Canada (UCC). The potential of Knox College to serve as the key theological centre for the whole church was close to being realized, except for the fact that thirty one percent of Presbyterian members voted non-concurrence, choosing thereby to remain Presbyterians.Given this minority, two critically important issues had to be resolved. Would non-concurring members of any of the denominations retain the denominational identity or would the denominational identities be assumed by the UCC? And would the Knox College facility with its hefty endowment and just mortgage-free be retained by the non-concurring Presbyterians or become part of the UCC?Politics ruled the day. In the end Parliament rejected the notion of non-concurrent members retaining the identity of their denomination. On the Knox issue, the province of Ontario had responsibility for determining property matters. Its Legislature resolved its reservation about the first issue by granting the new Knox building (but not the Principal’s residence) to the non-concurring minority.The Dominion Properties Commission followed suit by granting both the Charter and the bulk of the Knox endowment to the minority, while the school’s Caven Library was put under shared control. (The struggle to reach this conclusion is described in Cousland’s volume pp. 49-55.) Totally new faculty and board members were quickly appointed to manage the College for the continuing Presbyterians.Unionists lamented but Gandier remained gracious – even when the new appointees replaced him in the Principal’s office. Presbyterians and Unionists were entitled to three years of shared occupancy of the facility. Meanwhile the Unionists – the entire old Knox faculty, board and senate, and 80% of students, along with denominational officers – re-organized by quickly launching “Union Theological College” – for now lodged in the Knox facility.A "New" Theological SchoolOn April 10, 1927, the UCC’s General Council Executive incorporated the new college and authorized it:To enter into the same relations with Victoria as there existed between Knox College and Victoria University and to alter those relations in any way that was mutually agreed upon by Union College and Victoria University; and to unite with Victoria so as to form with its Faculty of Theology a Theological College of the United Church of Canada under terms and with powers determined by the General Council of the United Church. [And] to enter into federation with the University of Toronto. [The latter was enacted by UofT governors on June 30, 1927]In effect continuity between the “new” Union Theological College and Victoria’s Faculty of Theology was complete. As stated by Old Testament Professor and later Emmanuel Principal Richard Davidson: “Union Theological College is essentially ‘Old Knox’; only it bears a new name. It is Knox College continuing in the United Church and under a new name carries forwards its tradition, spirit, and service within the United Church.”Amalgamating “Old Knox” and Victoria Faculty of TheologyThe formal amalgamation of the two entities was next – now looking to integrate on the Victoria campus. Numerous aspects preceded the event. Joint classes, a common course of study, common worship, shared meals, a single curriculum – all indicated the chosen direction of both schools. The first joint convocation and graduation took place in the UofT Convocation Hall in 1926.But if amalgamated, in what way would the theological school relate to Victoria University. Previously Knox College was autonomous, but had close, informal relations with the University College Arts faculty? Victoria’s Chancellor Richard Bowles envisioned the solution as follows:I made it clear to the friend in [“old”] Knox that if Knox did not come in [to the UCC] I believed the policy of the new Church would be to bring the present Knox Faculty and students over to Victoria and continue in a new theological building in the very closest relations possible with the Arts College the work practically as it is now going on in Victoria…. A form of government which would unite the two as the property of one Church exercising its teaching functions in two directions was imperative. (Cousland, p. 59)Principal Gandier was, however, concerned to ensure that the theological entity within the Victoria arrangement would have a good degree of autonomy – as Knox had enjoyed in its relationship with University College. The latter institution was not faith-based as the former was. University College gave Arts students aiming towards ministry in the Presbyterian Church the window on the larger (secular) world needed by “learned” ministers of Presbyterian heritage, while Knox as faith-based seminary enabled theologs to deepen and further inform their faith and equip them for the practice of ministry.Faith-Based Education and the AlternativeIn his own way, Gandier may have been interpreting the institutional/organizational task through the quaerens ut intellectum – faith seeking understanding lens of Anselm of Canterbury. A seminary is a church-connected, faith-based organization dedicated to pursuing aggressively a deeper understanding of the Holy One who has called the school into existence through the faith of the community, i.e. church.The Arts college, may, as Victoria was and still is, be connected to the Church and honour "Christian principles" as 19th century forebears advocated, but it will pursue knowledge for its own sake as a core humanizing endeavor. It’s founders had clearly respected this humanistic role.But a faith-based theological college has a different motivation, usually manifested by close relationship with the church - faith communities. Says Canadian theologian Douglas Hall:“If it is truly faith, Anselm insists, it will seek to understand what is believed …. Like the defiant boldness of a lover, the doing of theology entails a search that will not be deterred by the many obstacles that are certainly in the way of it. … There is a drive towards understanding built into faith itself, if it is really faith and not just sentimentality.” *Faith-based theological studies are different from Religious Studies offered in an Arts faculty. The difference between the two needs to be honoured structurally and in practice.What is not mentioned by Cousland is whether Gandier’s concern was also based on the simpler assumption that a theological faculty within a larger predominantly arts-oriented university would inevitably be at greater risk of being overwhelmed or diminished by the much larger Arts faculty.In 1925, Victoria’s Arts students numbered more than 600; while the number registered in theology at the time of the amalgamation of Union College and Vic Theology was 77 students. The asymmetrical relationship between Arts and Theology was substantial and obvious. Arguing for a relatively autonomous College – Emmanuel – alongside a much larger Arts College – Victoria – within Victoria University, federated within the University of Toronto may simply have been Gandier's practical way of trying to protect the special nature of faith-based education.On April 3, 1928 royal assent was given to the Ontario Legislature’s Act to replace the Victoria University Act of 1915. The new act declared:“Union Theological College and the Faculty of Theology of Victoria University ‘are hereby united and amalgamated into one theological college of Victoria University to be known as Emmanuel College.’” [Cousland, p. 67]Both the Board of Regents, with a slight majority of UCC-appointed members maintained the close relationship with the United Church and the Senate had overall responsibility for the University. Victoria College and Emmanuel College within Victoria University each had a Council “charged with general supervision of the life and work of that college.”“The powers given to the Emmanuel College Council did give some measure of autonomy that Dr. Gandier wanted, for while the business administration, general oversight, and degrees came under the larger body, theological education was under the direction of the theological college, and the church through its representative had the final word in the appointment of theological professors.” (Cousland, p. 70) Gandier’s concerns were largely met.Fund Raising Again, StillWith the organizational configuration sorted out, the whole University with Bowles as President and Gandier as Principal worked (again!) indefatigably to raise funds from church members and alumni of the University to add new accommodations for both the new college and students. Emmanuel located at 75 Queen’s Park Circle was opened formally February 28, 1931 and the residences including “Gandier-Bowles House” [of which I was Don in the 1967-1968 school year] were ready for the 1931/1932 sessions – a time of serious financial stress.Today, financial pressures continue. The future of faith-based theological education for the UCC – no matter how institutions are configured - is murky. It is clearly easier to fund the teaching of the much larger Arts colleges than to find money for theological schools.Societal culture and values have shifted dramatically from the 1930s. Loyalty to the denomination and organized Christianity is weakening. The result is that the United Church itself has been forced to cope with seriously diminished resources.Theological studies in UCC-recognized institutions in Edmonton, Winnipeg, Kingston, Saskatoon have had to be or are being severely curtailed or even terminated. Financial pressures and the inability of the Church to sustain grants have long had their impact on all the church-related theological schools – a problem addressed by the UCC General Council in 1968, 1986, 2006, and again currently, but without lasting solutions.It seems unlikely that the Church can contribute much to solving the financial challenges of the several recognized UCC schools. Is it likely that UCC ministers – like the Methodist preachers of the 19th Century - might pledge half their salary to supporting the school or that another Gandier will emerge to inspire the kind of generous giving that built both Knox and Emmanuel College buildings?The United Church is not alone in this dilemma. Protestant churches of the ecumenical persuasion may no longer be able to afford “their own” theological schools the way it has been.Currently, Toronto School of Theology includes two Anglican schools, one Presbyterian and one United theological school. There are also three Roman Catholic theological institutions. In Hamilton, Baptists have a school and in Waterloo there is a Lutheran seminary. Toronto School of Theology is a step towards greater cooperation among seven school. More steps will doubtless be required.Does Theological Education Have a Future?Are members and leaders of church and schools thinking about how the “faith seeking knowledge” challenges of today and the critical needs of the future are going to be addressed or will these institutions just continue to fade one after the other?For the United Church, Cousland’s story of the founding of Emmanuel College is a gift and a prod. Our forebears modeled for us the urgency and their determination to provide both general education to meet societal needs and theological education, in particular, to equip the faithful for informed participation in God’s mission.Today’s urgency, I believe, is to discern sustainable ways to raise up and empower leaders through educational communities where faith can continue to seek knowledge. More to come.....~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~*Hall, Douglas J., Thinking the Faith. Minneapolis, Augsburg Press. 1989. P. 255